Beyond the Ban: Leading Your School Toward True AI Literacy and Cognitive Growth

Let’s name the reality many principals are living in right now: confused! The conversation around artificial intelligence in schools has quietly shifted. We are no longer asking, “How do we block this?” The real question has become, “How do we lead through it?” According to a recent Harvard University survey, nearly 87.5% of undergraduates are already using generative AI, with many relying on it to bypass foundational learning tasks such as reading assignments or attending office hours (Hirabayashi et al., 2024). While this data comes from higher education, K–12 leaders know what it signals: the habits students form now will shape how they think later.

At this point, access is no longer the problem. Cognitive engagement is. Students can open an AI tool in seconds, but that ease has exposed a deeper challenge: cognitive engagement. Without intentional AI literacy strategies, we risk graduating students who are fluent in prompting technology yet underprepared to think critically, reason deeply, or take ownership of their learning. This isn’t about whether AI belongs in schools because it’s already here. The real question is whether we are equipping students to use it as a thinking partner rather than a shortcut.

Why Unchecked AI Use Poses a Cognitive Risk

Simply allowing students to use AI does not guarantee learning. In fact, without clear instructional guardrails, it can quietly undermine it.

The brain activity gap.

A study conducted by researchers at MIT and Wellesley College found that students who used AI to draft essays showed significantly lower brain activity than students who wrote without AI. However, the study also revealed an important nuance: when students wrote an initial draft first and then used AI to critique, revise, or expand their thinking, brain activity actually increased (Schwartz, 2025). The takeaway for school leaders is clear: timing matters.

The illusion of competence.

Research on novice programmers found that students who relied on ChatGPT to generate full solutions often earned higher task scores yet demonstrated weaker conceptual understanding than peers who worked through the problems independently (Chen et al., 2025). In other words, performance improved while learning declined.

Ei360: Leading through AI

Shallow interaction patterns.

Further analysis of student–AI collaboration shows that many interactions fall into an “instruct, serve, repeat” loop. Rather than functioning as a thinking partner, AI becomes an “obedient follower,” offering answers without prompting deeper reasoning or productive struggle (Saqr et al., 2025). This dynamic limits true cognitive engagement and learning synergy.

Reframing the Goal: What Does AI Literacy Actually Mean?

If bans aren’t the answer, clarity is.

Dr. Med Kharbach defines an AI-literate student as one who uses AI in constructive, creative, and responsible ways and not simply as a shortcut to completion (Kharbach, 2026).

An AI-literate student does not copy and paste. Instead, they:

Use AI as a thinking partner, asking it to challenge ideas or surface counterarguments rather than generate original thinking from scratch (Kharbach, 2026).

Verify information, understanding that AI can hallucinate data and fabricate sources, and therefore cross-check claims against trusted references (Kharbach, 2026).

Retain ownership, using AI for feedback, language refinement, or organization while keeping core ideas and reasoning firmly human (Kharbach, 2026).

This distinction matters because it moves AI from a replacement for thinking to a scaffold for it.

What Principals Can Do: Evidence-Based Strategies That Work

School leaders don’t need more theory. They need practical, research-aligned moves they can guide instructional teams to implement.

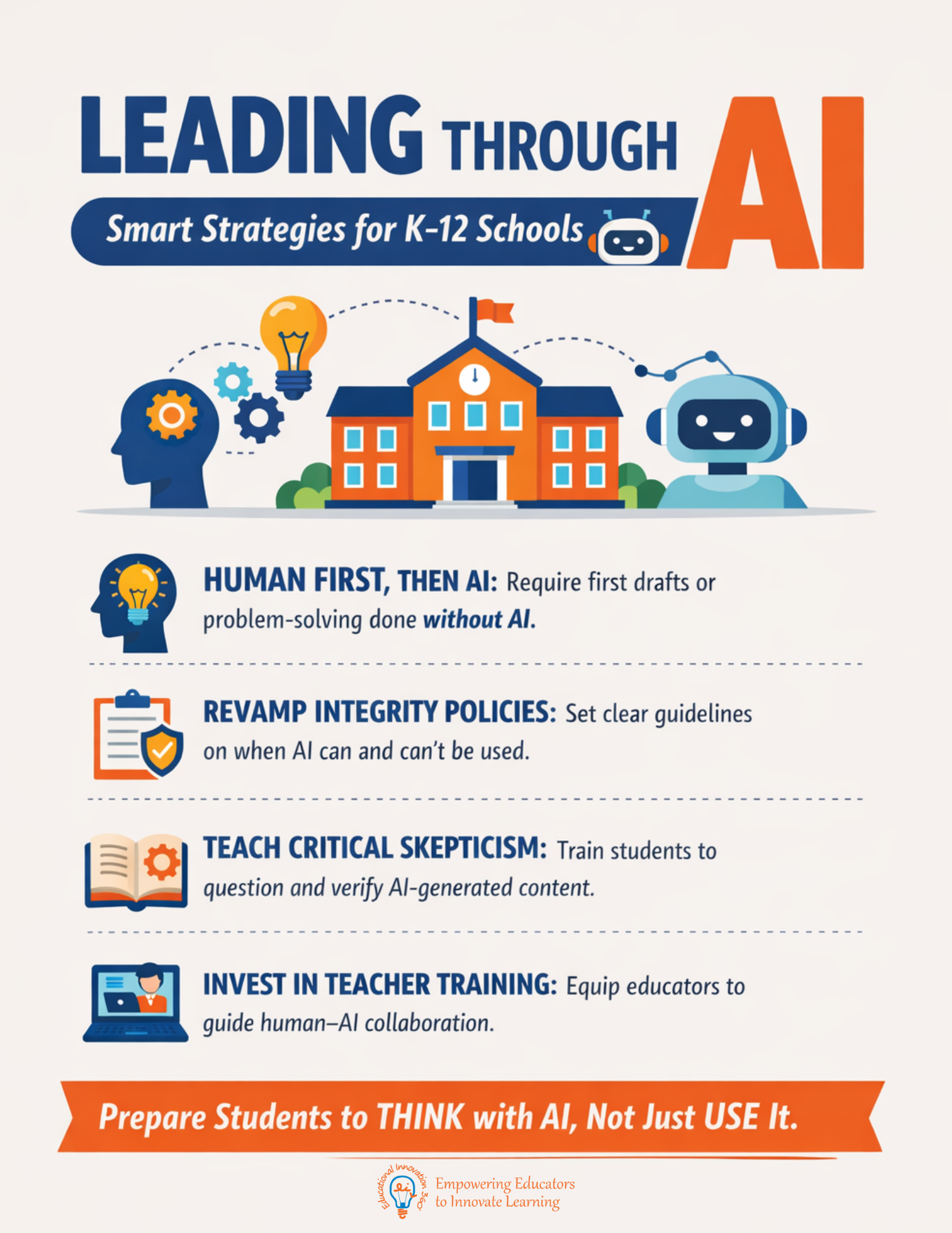

1. Enforce a “Human First” Rule

Drawing directly from MIT’s findings, schools should require that first drafts, initial problem-solving attempts, or original responses be completed without AI. This activates the neural pathways associated with reasoning and critical thinking before technology enters the process (Schwartz, 2025).

2. Teach Prompting as a Cognitive Skill

Prompt engineering, when taught intentionally, becomes far more than learning how to “ask better questions.” Teaching students to craft purposeful, precise prompts can reduce extraneous cognitive load, which is the mental energy wasted on irrelevant effort, while increasing germane cognitive load, the kind of thinking that directly supports learning and deep understanding (Nagori et al., 2025). In this context, prompting is not a shortcut; it is a disciplined thinking skill.

3. Use AI to Support Metacognition, Not Answers

AI is most powerful when it scaffolds how students think. Intelligent Tutoring Systems and learning analytics tools can provide feedback on learning processes, not just final products (Tsakeni et al., 2025). Reflective journals that document AI interactions help students shift from passive users to critical evaluators of technology (Hingle & Johri, 2024).

Strategic Next Steps for School Leaders

Step 1: Address the equity gap.

Surveys show that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are significantly less likely to afford premium AI tools, which often include stronger reasoning capabilities (Hirabayashi et al., 2024). Equity now includes access to approved, high-quality AI resources.

Step 2: Modernize academic integrity policies.

Move beyond prohibition lists. Instead, define when AI use is appropriate (feedback, brainstorming, revision) and when it is restricted (first drafts, assessments, factual recall). Require transparency around how AI was used (Kharbach, 2026).

Step 3: Invest in teacher learning, reach out to Ei360!

Teachers cannot guide what they do not understand. Professional learning should help educators shift from content delivery to facilitating productive human–AI collaboration (Tsakeni et al., 2025).

Step 4: Teach healthy skepticism.

Curriculum must explicitly address AI bias, hallucinations, and limitations. Students should be trained to question, verify, and interrogate AI outputs every time (Kharbach, 2026).

The Leadership Moment Before Us

This moment does not call for fear or restriction. It calls for leadership.

When principals lead with intention, attending to timing, cognition, and equity, AI becomes what it was always meant to be: a tool that strengthens human intelligence rather than replacing it. With the right structures in place, schools can move beyond teaching students how to use AI and instead develop learners who think deeply, act responsibly, and maintain ownership of their learning in a world where AI is everywhere. This is our moment to lead with clarity and purpose. And yes, we can do this, and we can do it well.

References

Chen, R., Jiang, S., Shen, J., Moon, A., & Wei, L. (2025). Examining the usage of generative AI models in student learning activities for software programming. arXiv.

Hingle, A., & Johri, A. (2024). Mapping students' AI literacy framing and learning through reflective journals. arXiv.

Hirabayashi, S., Jain, R., Jurković, N., & Wu, G. (2024). Harvard undergraduate survey on generative AI. Harvard Undergraduate Association.

Kharbach, M. (2026). What AI-literate students do differently. Med Kharbach, PhD.

Nagori, V., Mahmud, S. A., & Iyer, L. (2025). Impact of prompt engineering skills on cognitive load: A qualitative approach. AMCIS 2025 Proceedings.

Saqr, M., Misiejuk, K., & López-Pernas, S. (2025). Human–AI collaboration or obedient and often clueless AI in instruct, serve, repeat dynamics? arXiv.

Schwartz, S. (2025, June 26). Brain activity is lower for writers who use AI. What that means for students. Education Week.

Tsakeni, M., Nwafor, S. C., Mosia, M., & Egara, F. O. (2025). Mapping the scaffolding of metacognition and learning by AI tools in STEM classrooms: A bibliometric–systematic review approach (2005–2025). Journal of Intelligence.